Deglobalisation is an awkward word for a phenomenon that makes investors and businesses anxious. The last time the world experienced it on a significant scale, between 1914 and 1945, was one of the darkest periods in history, encompassing two world wars, economic depression and trade protectionism.

"This a nervous time not just for large multinationals, but also for many small and medium-sized businesses that have embraced international collaboration."

So far, this time around, we are not in that territory. It is clear, though, that the recent wave of globalisation – loosely defined as the free flow of trade, capital, people, technology and ideas across borders – has stalled since the financial crisis. Less certain is how far it may go into reverse.

That makes this a nervous time not just for large multinationals, but also for many small and medium-sized businesses that have embraced exporting, outsourcing, joint ventures or other forms of international collaboration. They must navigate an increasingly complex and hazardous landscape.

Globalisation is credited with helping the world economy to expand at its fastest pace in recorded history in the decades before 2008, as well as lifting millions out of poverty in the emerging world. It has lowered inflation and interest rates, by curbing labour costs, and boosted corporate profits.

Workers in the developed world, however, have not shared these benefits. Many blame globalisation for job insecurity and stagnant wages. Although economists point to automation as a likelier cause, fear of globalisation has created an anti-establishment backlash that swept Donald Trump to the US presidency on a protectionist ticket, fuelled the UK’s Brexit vote and has aided populist movements in countries including Germany and the Netherlands.

Globalisation goes through cycles and appears to have reached another turning point. The first wave between 1850 and 1914 was marked by industralisation, urbanisation and new transport and communications technologies. Trade reached 38% of global gross domestic product by 1914, but by 1945 that had dropped to 7% as a result of isolationist policies, according to a Barclays analysis of data from the US’s National Bureau of Economic Research.

A second wave of globalisation, from 1945 to 1990, saw world trade grow alongside the postwar economic recovery, accompanied by the creation of institutions and agreements such as the International Monetary Fund, Word Bank and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Since 1990 there has been a period that some call “hyperglobalisation”, marked by the demise of the Soviet Union, privatisation, deregulation and rapid advances in information and communications technology. Its main beneficiaries were the emerging economies, which became increasingly integrated into complex value chains.

As economist Richard Baldwin notes, the nature of globalisation has changed. Digital control of supply chains has allowed industrial production to be split up into dozens or hundreds of stages, which are then allocated to producers around the globe according to efficiency and cost.

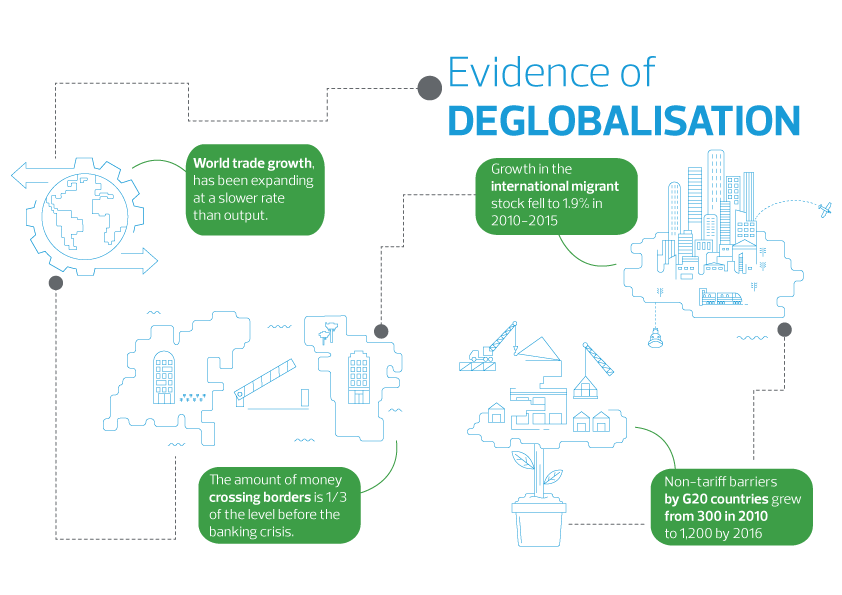

What evidence is there of deglobalisation? World trade growth, which easily outpaced global GDP growth in the two decades before the crisis, has been expanding at a slower rate than output. Trade as a proportion of global GDP – a measure of openness – overtook its 1914 peak only in the mid-2000s, according to the Barclays analysis. It reached nearly 50% by the time of the crisis and has not, so far, fallen a great deal: it dipped to 47% in 2015.

Capital flows, however, have fallen sharply. The amount of money crossing borders is one-third of the level seen before the crisis, mainly because banks have reined in their lending, according to McKinsey Global Institute. That is not necessarily a bad thing - excess capital flows were one of the primary drivers of the crisis — though growth will be held back if capital cannot move efficiently across borders.

Migration has prompted an anti-immigrant backlash in many countries, but has slowed since the crisis. According to the United Nations, growth in the international migrant stock increased from an average 2% a year in 2000-2005 to 3% in 2005-2010, but fell to 1.9% in 2010-2015.

There has not been a widespread, 1930s-style increase in import tariffs, though there is a subtler rise in other forms of protectionism. The World Trade Organisation calculates that non-tariff barriers operated by G20 countries, such as anti-dumping measures, grew from about 300 in 2010 to more than 1,200 by 2016.

It is too early to tell whether this will turn into a sustained period of deglobalisation. Ruchir Sharma, chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley, warns that when a reversal begins, “what history tells us is that this could last for many, many years".

A few factors may guard against extreme deglobalisation. These days it is not only manufactured goods that cross borders, but also knowhow, data and skills – much harder to control. The halt to globalisation may have more to do with exhaustion of outsourcing opportunities, slowing pace of liberalisation and weak investment than protectionism.

President Trump, despite his “America first” rhetoric, has so far not done much on trade apart from pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiated by the Obama administration. If he restricts steel imports, for example, that might help the US steel industry but at the expense of higher costs for other industries such as cars. Import barriers may be more likely to encourage automation than create US jobs.

There may be life yet in liberalisation. This year the EU and Japan reached agreement in principle on a trade deal, following the recent EU-Canada accord. After US withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Japan has set out to reach a deal with other TPP members.

Companies are used to living with complexity. Despite globalisation, they know that countries vary considerably in the ease of doing business. Many have their own rules and hidden barriers. In the current climate, there is an even greater need to research markets individually and watch for policy shifts.

"A big wave of deglobalisation would of course have serious implications for companies, not least the time and cost they would have to devote to adjusting to the new environment."

In manufacturing, many companies have already reshored elements of production, not because of an anti-globalisation backlash but because of rising costs, notably in China. New technologies such as 3D printing allow for smaller factories to produce personalised goods on demand.

A big wave of deglobalisation would of course have serious implications for companies, not least the time and cost they would have to devote to adjusting to the new environment. For now, though, cautious engagement seems a wiser strategy than peremptory withdrawal from international markets.