Author: NIU Yuanhao

It was not unusual for Brazilians to have big families of four or five children in 1980s. Every couple had on average more than three children during the decade. However, families are much smaller nowadays and some urban young couples have no children at all.

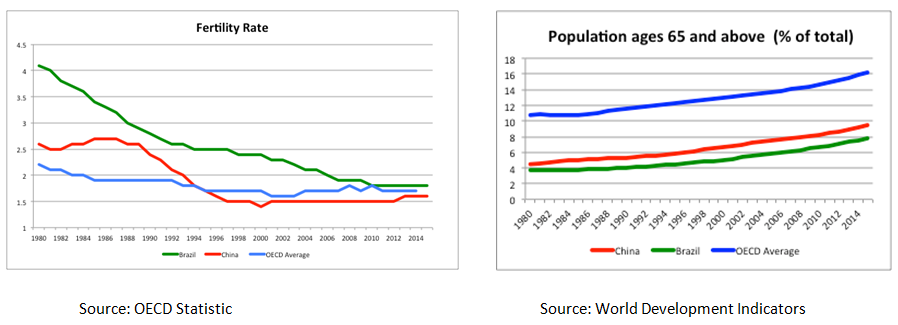

This is part of the big demographic transitions in Brazil. The fertility rate has halved in the past thirty years and it is below two in the recent survey. At the same time, life expectancy has risen from 62 years old in 1980 to above 74 years old in 2015. The Brazilian society is populated by more elders and less youth. By 2050, 38% percent of the Brazilian population is estimated to be aged 65 and above, compared with 7.6% in 2010. The aging population poses series of challenges for the government and civil society.

Pension Reforms in Brazil

The aging population has an immediate consequence to the pension system. With more elders withdraw money and fewer young workers contribute, the sustainability of the social security account is at stake. The Brazilian government is spending a significant proportion of their budget on subsidizing pension plans, which is especially burdensome for the current tight fiscal environment.

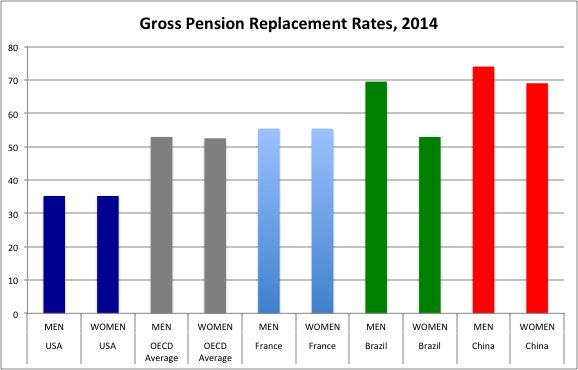

Brazil has one of the world's most generous pension systems. When the country transited to democracy in the late 1980s, the constitution entitled every male over 65 and female over 60 rights for a pension indexed to the minimum wage, regardless of the previous contribution. For those who had paid in the system, they were able to withdraw at an earlier age. This resulted in an average retirement age around 55 years old for Brazil. The widows and widowers were also entitled to receive the full pension of their deceased significant other. With prolonging life expectancy, these well-intended policies became expensive for the government to maintain.

However, pension reform is a very contentious issue in Brazil due to the large presence of labor unions. The major pension reform was initiated in 1998 under the government of Cardoso, aiming to reduce social security account deficit. Brazil went through a serious currency and economic crisis at that time. The reform tightened eligibility requirement for full pension by requiring certain minimum years of contribution. New formulas were used to calculate pension benefits.

Source: OECD (Note: The gross replacement rate is defined as gross pension entitlement divided by gross pre-retirement earnings.)

The current government of Temer is making similar attempts. Interestingly, this is happening also at a time of deep economic recession. One of the proposals is to raise minimum age to 65 years old for a full pension, which is common to most other nations. Similar measure was proposed by Cardoso in 1998 and was rejected in Congress. The entitlements of widows and other non-contributory pensions will also be reduced. Although Temer's plan strategically includes transitions rules, these measures are naturally unpopular within a politically deep divided country. With the new scandals of the administration and continuing high level of political uncertainty, the pension reform is likely to encounter more difficulties in the legislative process.

Pension Reforms in China

The demographic challenge is shared by China. Its high fertility rate dropped sharply in the late 1970s when the one-child policy was imposed. The policy was strict in urban areas and more relaxed in rural areas. The fertility rate stabilized around 1.5 for more than a decade. During the time period, life expectancy has raised for 10 years. People aged over 60 accounts for 13.26% percent of the population according to 2010 census. The figure is estimated to exceed 20% by 2030.

Nevertheless, the Chinese government does not share the fiscal pressure to control expenditure. China is in the process of establishing a unified comprehensive pension system, combining the existing plans in urban enterprises, public sectors and rural areas. The pension plans historically concentrated on the urbanized areas, whereas many parts of countryside await access to social security benefits. The system lacks sufficient funding since contribution is not always compulsory unless the employer requires. The poor performance of pension funds aggravates the situation. The fund managers are only allowed to invest in bank deposit, government bonds or other low-yield assets. The government has control over the amount of pension payment and its level is not indexed. There also exist no worker union that can exert public pressure, comparable to a Brazilian scale.

Gradually raising the retirement age is the most discussed alternative in China. Currently, the retirement age for a male is 60 and it ranges from 50 to 55 for females depending on occupation. The social security administration proposed to gradually delay the retirement to 65 years old for male and female in future. The proposal is widely discussed but has not put into the legislature.

Adjustments beyond Pension Reforms

The most immediate macroeconomic implication is the reduced labor supply. China has long enjoyed the demographic dividend relates to abundant labor surplus. One of the driving forces of China's economic growth was labor-intense export manufacturing industries. Economists argue China has already passed the Lewis Turning Point, where they could no longer rely on cheap labor. In response to this, Chinese government modified one-child policy to two-child policy in 2015. Statistics has shown the slight jump in the number of newborn babies. But it is unclear if this trend will sustain in future. In the case of Brazil, the unemployment rate is at record high level over 13 percent. If the economy picks up momentum, the tightening of labor market is inevitable.

A common phenomenon observed in aging societies is increased saving rate and lower personal consumption. The prototypical economy is the one of Japan. People save more in their prime-earning years in order to finance their retirement. Low personal consumption jeopardizes economic growth. In addition, with fewer children, parents might want to save more since they may receive less support from children. China had high saving, high public investment but low domestic consumption. This is likely to counteract the government's effort to boost domestic consumption.

Another undeniable fact of an aging population is the surging demanding for medical and health care services. This creates huge growth potentials for pharmaceutical and related industries. Both Brazil and China have a large public health sector. A significant amount of population relies on public health services. The surplus for China's state-run health insurance has been shrinking. The situation might be tougher in the years to come. In the Brazilian case, the government has capped fiscal spending for the next twenty years. The shortage for healthcare provision will only increase. This is likely to exacerbate the tensions of unfulfilled healthcare demands.