Author: Dr Mathew Hampshire-Waugh, Founder of Net-Zero Consulting Services LTD

A new paradigm

Less than a decade ago, electric vehicles (EVs) were regarded by most as an unprofitable side-show whose main function lay in helping auto manufacturers meet tightening emissions standards. Fast forward to today: EVs have crossed 10% of new car sales, the sale of combustion engines is already banned in the UK, Canada, California, and the EU by the close of the next decade, and most car companies expect to be predominantly electric by 2035.

So, what forced this paradigm shift? What does it mean for the future of the automotive industry? And how do we ensure a sustainable and equitable transition?

A warning triangle up ahead

The signs that a new paradigm might be about to sweep the car industry became evident in late 2015 when three key trends across technology, trust, and regulation created a clear warning triangle.

First came proof of technology, starting with the celebrity endorsement and acceleration in sales for the Toyota Prius in the late noughties. This was swiftly followed by the launch of Elon Musk’s premium offering, the Tesla Roadster, in 2008, and the Nissan leaf in 2010 – the world’s first fully electric mass-market vehicle. These ground-breaking cars were proof of concept that electric vehicle technology could work, the cars might sell, and just maybe the economics of production could stack up.

Fast forward to September 2015; the ´diesel-gate´ scandal broke, exposing emissions cheating in the auto industry. This was done using defeat devices designed to ace emissions testing in the lab, but allowing vehicles much higher levels of pollution during real-world driving. Public trust in combustion engines, and the incumbent car industry, was dealt a severe blow. Regulation on vehicle emissions in Europe, the US, and China was already tightening. Diesel-gate emboldened politicians to notch that legislation up another gear.

Navigating the transition

In 2015, even the most optimistic forecasts predicted electric vehicles might reach just 10-20% of new car sales by 2030. , Today, many of the largest car manufacturers – such as Volvo, Mercedes, and Bentley - expect to be 100% electric by 2030, with other leading manufacturers closely following. Further to this, Tesla’s market value is now equivalent to all other car manufacturers combined. The market has spoken: the future of driving is electric.

Exactly how the transition will evolve for the incumbents, new entrants, and the supply chain is still uncertain - but the same warning triangle provides a preliminary roadmap:

Short-term: Expect further tightening of global tailpipe emissions regulations, increasing zero-emissions car quotas, and greater government-led incentivisation - all driven by concerns around climate change, air pollution, and the road to a more sustainable economy. The US Inflation Reduction Act, finally signed off in 2022, is the latest piece of legislation to bolster the roll-out of electric vehicles. This includes over $30 billion earmarked for tax breaks, more charging stations, and government vehicle procurement.

Mid-term: Technology will further improve the cost and performance of electric cars. A battery for a long-range EV costs around $13,000 today. Simply introducing incremental improvements to battery materials, battery management systems, and production efficiencies, very quickly reduces that cost to below $10,000. As production moves to next-generation battery technology, such as solid-state, the costs will plummet towards $5,000.

Long-term: These trends will build trust, and the market moves 100% electric when EVs retail at the same price as combustion vehicles, cost $1,000 less to run each year, have 400+ miles of range, ten-minute charge times, and plentiful charging locations.

Creating a truly sustainable value chain

How do we create a product, a supply-base, and an end-of-life prospect which supports the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) on climate change, sustainable cities, responsible production, quality jobs, and social, economic, and environmental equality? And how do we do create this change whilst creating economic value?

The product specification

Electric vehicles are not new; in fact, the first was brought to market in 1890 and, by the turn of the century, electric cars were outselling their gasoline counterparts. However, the ingenuity of Henry Ford and his pioneering mass-production techniques for the gasoline-powered Model T signalled the end for the electric vehicle market which simply could not compete on cost.

A century later, the invention of the lithium-ion battery has revolutionised the cost of production and efficiency of modern electric cars. It is this efficiency which creates a product fit for purpose.

The modern electric car is more than 75% efficient, whereas a combustion engine vehicle utilises just 25% of the energy from gasoline (the rest is wasted in heat and noise). This efficiency is why an electric car averages 1 tonne fewer CO2 emission for each year of driving - even when charged by grid electricity partly fed by fossil fuels. Yes, making the battery itself releases more CO2 during production; however, over the life of the vehicle, an EV will save more than 10 tonnes of CO2 when compared to the equivalent combustion engine car.

Not to mention that electric vehicles provide rapid acceleration, minimal maintenance, and extra luggage space - ticking all the boxes for emissions credentials and product performance. Put simply, electric vehicles are great today, but importantly they also enable Net-Zero tomorrow as grid electricity becomes increasingly fed by renewables.

There are alternative technologies out there, such as hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles, but due to losses associated with producing hydrogen from renewable electricity, and losses in the fuel-cell “engine” of the car, the combined efficiency is limited to around 35%. This creates higher running costs and requires double the number of solar panels or wind turbines to run the vehicle.

The long-held belief of Automotive CEOs and analysts alike was that electric vehicles would destroy the profits of traditional car manufacturers – that batteries were too expensive, and consumers would not pay a premium. However, the tide is turning, with recent industry comments and analysis showing that electric cars may prove just as profitable as their petrol-fuelled predecessors, if not more so. Innovation and economy of scale are driving battery costs down by 30% every time that production is doubled. Since electric vehicles contain half as many parts as combustion vehicles, with ten-fold fewer moving parts, manufacturing platforms can take advantage of the lower complexity to boost efficiency and further reduce cost – a move which Henry Ford would very much approve of.

The supply chain requirements

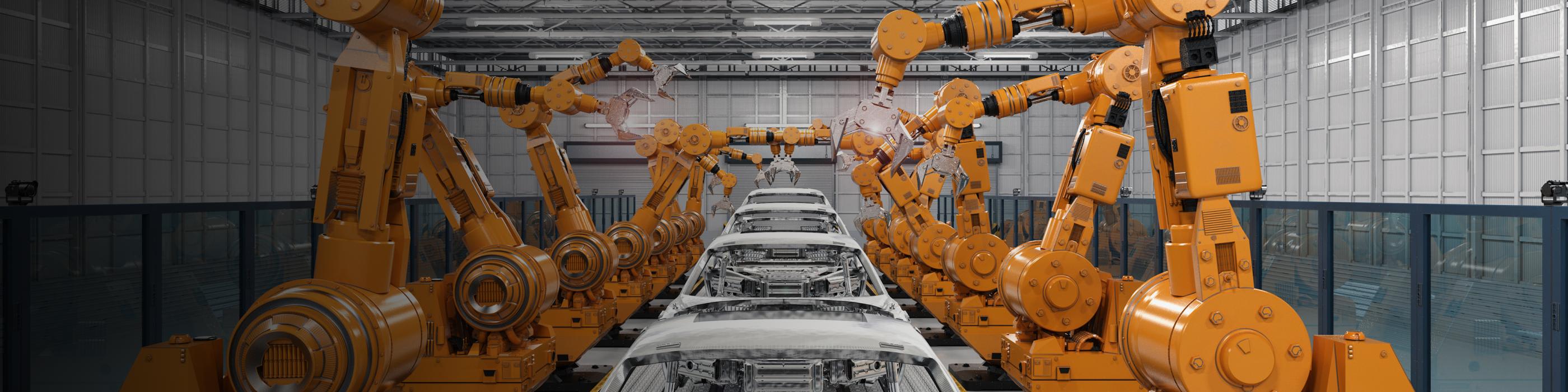

Car companies are vying to take their place in the burgeoning electric car market; a market that is bringing with it a complete overhaul of manufacturing platforms and supply chains. Getting the transition right from the start should be at the forefront of industry thinking, not just from a profitability perspective, but also to ensure a sustainable, just, and equitable transition for all.

As combustion engines are replaced by batteries and electric motors, this creates new demand for raw materials such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, and copper. Resources are plentiful in the Earth’s crust. To replace each of the 1.4 billion cars on the road today with long range electric vehicles would consume around 15% of the Earth’s lithium. But ensuring a robust, stable, and ethical supply of these materials is imperative if the explosion in demand is to be met. Accordingly, cobalt has been the recipient of ethical concern because 70% of global supply is sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where it accounts for a third of national GDP. However, 20% of output from the DRC comes from small-scale, so-called “artisanal” mining, or corrupt institutions linked to child labour, safety issues, and environmental abuse.

The mining of new energy materials for net-zero technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, and, of course, lithium-ion batteries, will require a tiny fraction of the area currently exploited for fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas. However, we must ensure a sustainable and just transition from the start if we are to avoid the further exploitation of resources and labour in developing countries. Sustainable supply-chain frameworks with the necessary transparency, due diligence, traceability, and accountability, are top priority.

The industry must responsibly support the transition to net-zero over the coming decades. Car companies must measure and manage their own green-house gas emissions, enable net-zero transport through electrification of products, and engage the supply-chain to drive the required investment and technical innovation in net-zero materials and components.

The scale, complexity, and political-economic reach of the automotive industry means it is uniquely positioned to support rapid decarbonization throughout the industrial complex, energy markets, and the transport sector.

The end-of-life proposition

As electrification displaces combustion in the automotive industry and the world pushes towards sustainability and a circular economy, the end-of-life treatment of cars becomes increasingly important. Whilst many studies show that EV batteries are outlasting the remainder of the vehicle, by the next decade there will be a fast-growing need to close the loop on vehicle manufacturing.

Reusing could be the first option, with EV batteries refurbished to 70% of original performance and re-purposed in residential or grid energy storage applications.

Recycling of spent batteries to extract the valuable metals is already possible and nearly economically viable. Creating the correct mix of regulation, incentivisation, and infrastructure will support a future battery recycling industry.

Reduce is the final “R”. Given there are already 1.4 billion vehicles in the world, the automotive industry must come to terms with the need for peak production. In addition, it should support better integration of driving with walking, cycling, and public transport through mobility as a service. It has a crucial part to play in helping to create a seamless transport system accessible that is affordable for all. In doing so, the automotive industry moves from being an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) towards being a service provider.

Less manufacturing, more service

We can ask as car production inevitably peaks, which of the existing OEMs can successfully transition from car manufacturer to mobility operator, and what role can the industry play in this new market?

With even the lowest-cost electric vehicles offering instant torque and rapid acceleration, the days of differentiating cars on engine size, or number of cylinders, are nearing an end. Instead, consumers will increasingly focus on service, flexibility, and interactivity.

The car market will fragment into a mix of private ownership, leasing, and subscription-based access. Vehicle platforms will become a physical extension of your virtual world, competing though connected services such as:

- Integrated smart payment systems,

- Travel planning,

- Ease-of-access charging services,

- Navigation,

- Media,

- Remote working,

- Remote servicing,

- Back-up power provision,

- Real-time traffic-charging-parking management,

- Ride-sharing,

- Ride-hailing,

- Self-driving,

- And multi-modal transport connections… to name but a few.

As the automotive industry becomes less about manufacturing, and more about service, it should recognise value creation is not just for shareholders, but for all stakeholders. Embedding standards surrounding Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) pillars into the emerging corporate blueprint should mitigate risk, maximise opportunity, and create positive impact for all. Studies have shown that embedding sustainable business practices improves operational performance, company cash flows, and investor returns. With the network of action between governments, finance, industry, and individuals getting ever stronger, this should further reinforce sustainable value creation going forward.

Henry Ford once said, “If you always do what you always did, you’ll always get what you’ve always got”. With the automotive industry poised to enter a completely new paradigm, the incumbents must prepare for change. Nothing written in these paragraphs is novel; these trends have been spoken about for decades. However, a warning triangle is fast approaching – those companies still just playing lip-service to sustainability themes will quickly fall behind with technology, increasingly struggle to access human or economic capital, and will destroy their market share.

The next decade will prove pivotal. Car manufacturers, get onboard or get left behind.