When the European Commission quietly released its draft guidance on reporting “serious AI incidents” under the EU AI Act at the end of September, few expected the accompanying documents to be quite so granular or quite so demanding. But as Europe races ahead with the world’s most comprehensive AI regulatory regime, the message to businesses is unmistakable: incident reporting will not be a box-ticking exercise. It is to be treated as a central pillar of AI governance, with operational consequences that extend far beyond compliance teams.

The consultation on the guidance and the draft reporting template closed on 7 November 2025. The final version will shape the practical reality companies face as the EU AI Act’s incident regime becomes applicable in August 2026. For Dutch companies—many of whom now sit at the vanguard of European digitalisation—the implications are sweeping. At RSM Netherlands, we see the draft guidance not as a bureaucratic hurdle, but as a preview of how AI governance will evolve: more structured, data-heavy and deeply integrated with existing supervisory regimes. And, crucially, as a moment for businesses to secure an early advantage.

This article is written by Mourad Seghir ([email protected]) and Mario van den Broek ([email protected]). Mourad and Mario are part of RSM Netherlands Business Consulting Services with a specific focus on Supply Chain Management and Strategy

A sharper definition of “serious”

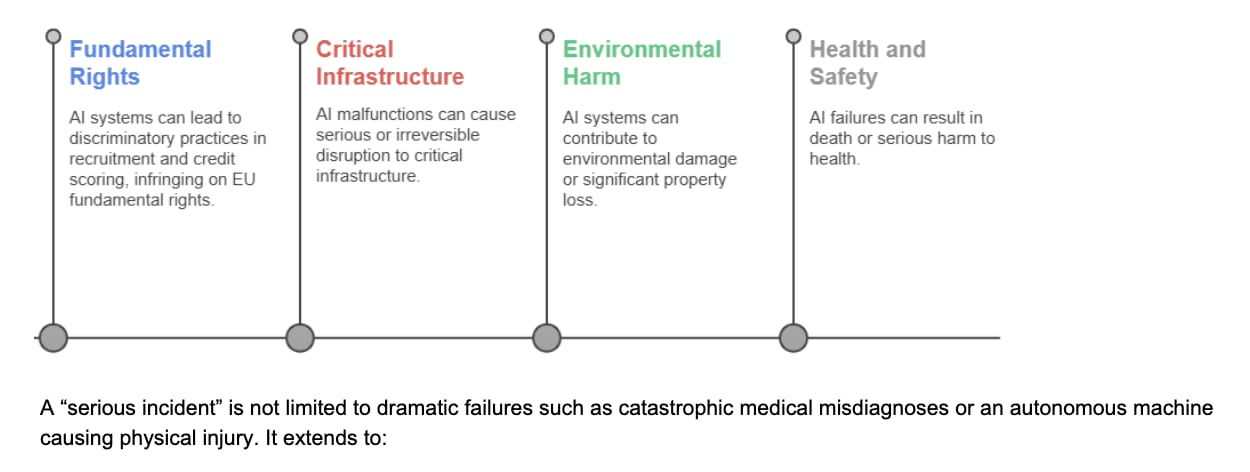

For months, legal teams across Europe have wrestled with the Act’s deceptively simple definition of a “serious incident.” The draft guidance brings both clarification and consequential expansion.

Importantly, the Commission underscores that an indirect causal link is enough to trigger the obligation. If an AI model’s output nudges a human decision-maker towards a harmful choice, the AI can still be considered causally connected. This expansion has material consequences. Many companies who believed they would escape incident-reporting duties—on the basis that “the AI isn’t making the decision”—may find themselves caught after all.

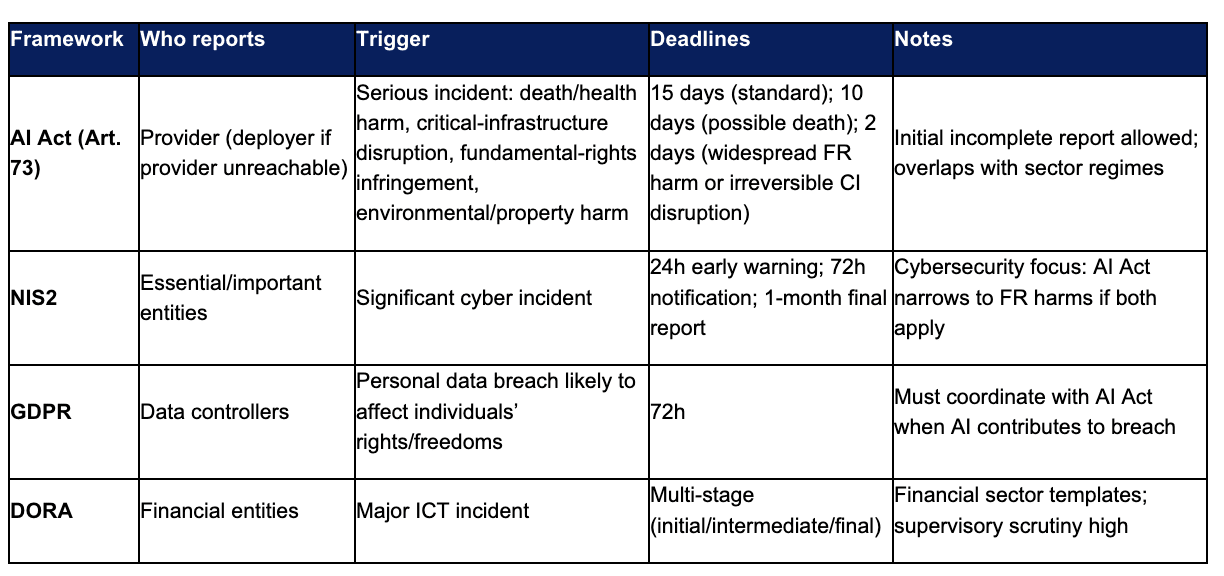

Where GDPR’s 72-hour notification window once set the tone, the AI Act adds far more nuance—and far more pressure. Under the draft guidance, 15 days from awareness is the standard deadline, 10 days where the incident “may have caused” a death, and 2 days where fundamental rights violations are widespread or where serious and irreversible disruption of critical infrastructure is at stake.

The EU acknowledges the practical difficulty of these windows, allowing companies to file an initial, incomplete report, followed later by further detail. Still, the obligations are intense. They effectively require businesses to identify, triage, investigate and escalate an AI-related anomaly within hours, not days.

The shorter windows—two days and ten days—will matter most for heavily digitised sectors: financial services, logistics, energy, healthcare, and public-sector contractors. These are also sectors already subject to other rapid-reporting regimes such as NIS2, DORA and GDPR. The draft guidance openly acknowledges this regulatory layering but offers only partial relief.

Where industries already have established incident-reporting channels—medical devices under the MDR/IVDR, ICT incidents under DORA, cybersecurity under NIS2—the AI Act’s reporting obligations narrow to fundamental-rights-related harms only. For everything else, companies must report under both frameworks. In practice, this means businesses need a unified evidence-collection spine feeding multiple regulatory inboxes.

Providers and deployers: shared responsibility, asymmetrical exposure

The AI Act draws a sharp line between providers (who place a high-risk AI system on the market) and deployers (who use it in operational environments). The draft guidance reinforces that both have obligations—but the weight falls, predictably, on providers.

- Providers must investigate incidents, preserve logs, avoid altering systems before notifying authorities, and file reports within the statutory windows. They must be ready to provide root-cause analysis, system identifiers, the number of affected users, and proposed remedial measures.

- Deployers, by contrast, must supervise AI operation, maintain input-data integrity, ensure human oversight, and—crucially—alert providers and authorities “without undue delay” if they believe a system may produce a serious risk. If the deployer cannot reach the provider, the deployer must report directly.

This asymmetry is already reshaping vendor contracts across Europe. In the U.S. and parts of Asia, AI procurement often emphasises performance metrics. Under EU rules, contracts must now specify incident-reporting cooperation, log-sharing rights, notification SLAs, and chains of accountability. For many companies, this is proving a significant redesign exercise—one that cannot be left until 2026.

How ready are businesses? Europe’s uneven landscape

Europe’s rapid legislative momentum hides a more fragmented reality: many businesses are still struggling with foundational digital capabilities. In 2024, Eurostat reported that:

These numbers reflect two truths. First, AI adoption is accelerating faster than many boards realised. Second, despite high adoption, readiness for Article 73–level incident reporting is low. Many organisations still lack several key items such as centralised logging and model-versioning systems, formal AI risk registers, mapped data flows for specific AI use cases, and escalation rules combining GDPR, NIS2, DORA and AI Act requirements. Without these foundations, the EU’s deadlines will be near-impossible to meet.

The Commission’s draft reporting template, released alongside the guidance, runs counter to any notion that reporting might be lightweight. For many businesses, providing this level of granularity within 48 hours—particularly when also navigating GDPR or NIS2 obligations—will require an entirely new discipline of evidence collection.

It is also striking that the Commission published a parallel template for General Purpose AI (GPAI) systems with systemic risk on 4 November 2025. Although not directly applicable to most businesses, many rely on GPAI embedded in third-party platforms. The expectation is clear: systems handling significant societal or economic risks require higher-order scrutiny.

The digital law challenge

Regulatory overlap is now unavoidable. The table below highlights the practical contrasts between the AI Act and other European reporting frameworks.

The operational implication is simple: companies must treat incident response as a single integrated function, regardless of which authority ultimately receives the report.

The Dutch dimension: regulatory architecture takes shape

Although the AI Act is EU-wide, implementation will depend on Member States’ supervisory structures. In the Netherlands, two authorities are currently the likeliest candidates for AI Act oversight:

- the Dutch DPA (Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens), given the connection to fundamental rights and data-driven harms; and

- the Authority for Digital Infrastructure (RDI), already involved in monitoring digital service providers and technical safety standards.

Sector supervisors—including DNB (for financial institutions), the Health and Youth Care Inspectorate, and the Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate—are also expected to play a role depending on the use case. The result will likely be a coordinated model, like the Netherlands’ arrangements for cybersecurity and digital-infrastructure supervision. Businesses must therefore prepare for multi-authority engagement, not a single reporting channel.

Forward thinking

For all its complexity, the EU’s draft guidance represents a necessary moment of clarity. It signals that AI governance will not be outsourced to compliance teams—it will become an operational discipline as fundamental as cybersecurity or data protection. Europe is moving quickly. The Netherlands is moving with it. And businesses that embrace this shift early will not simply avoid sanctions—they will strengthen their resilience, improve customer trust, and unlock competitive value in a market where oversight and transparency increasingly shape commercial success. At RSM Netherlands, our view is simple: companies that treat Article 73 as a strategic capability rather than a regulatory burden will be the ones that thrive in Europe’s new AI economy. And the window to build that capability—before the rules take full effect in August 2026—is closing fast.

RSM is a thought leader in the field of Supply Chain Management and Strategy matters including AI developments. We offer frequent insights through training and sharing of thought leadership based on a detailed knowledge of industry developments and practical applications in working with our customers. If you want to know more, please contact one of our consultants.