With the release of the Banking Royal Commission (BRC)’s interim report, a fresh wave of consumer backlash against the big four banks has surfaced along with cries for retribution, condemnation and large financial penalties.

In recent research undertaken by investment bank Morgan Stanley, Australia's big four banks are facing financial penalties and customer remediation programs totalling $1.3 billion through to the 2020 financial year.

These include:

- Commonwealth Bank (CBA)'s $700 million AML/CTF fine

- National Australia Bank (NAB), Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ) and (CBA) being forced by Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) to pay $120 million over bank bill interest rate rigging

- Westpac agreeing to refund 200,000 customers over failing to pass on discounts

- NAB highlighting a $100 million provision to cover "regulatory compliance investigations"

Are finance penalties effective?

Behavioural economics studies the effects of psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural and social factors on the economic decisions of individuals and institutions, and how those decisions vary from those implied by classical theory.

Behavioural economics is primarily concerned with the bounds of rationality of economic agents, how market decisions are made, and the mechanisms that drive choice. According to Shefrin (2002), the three prevalent themes in behavioural economics are:

- Heuristics: humans make 95% of their decisions using mental shortcuts or rules of thumb

- Framing: the collection of anecdotes and stereotypes that make up the mental filters individuals rely on to understand and respond to events

- Market inefficiencies: these include mis-pricing and non-rational decision making

To further understand the potential effectiveness of financial penalties, behavioural economic studies can be referenced to better understand how the misconduct, disclosed by the recent BRC’s interim report, were rationalised to have been allowed to go unpunished and determined to not be that serious.

Childcare

In their book, The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and the Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life, John List and Uri Gneezy detailed what happened when fines were introduced to selected childcare centres. Of the 10 childcare centres in Haifa, List and Gneezy selected six centres at random, introducing a small fine for parents that showed up more than 10 minutes late to pick up their children.

In childcare centres where the fine was introduced, parents immediately started showing up late, with tardiness levels eventually levelling out at about twice the pre-fine level. In the remaining four childcare centres that remained fine-free, tardiness didn’t change at all.

The picture that emerged from this experiment, co-authored with Aldo Rustichini, was that a parent’s decision to be on time was impacted by non-financial factors. As soon as there was the option to pay a fine, it appeared to justify the potential guilt of, for example, inconveniencing the workers at the childcare centre.

Libraries

In 2017, the City of Sydney Council undertook a trial which led to a moratorium on library fines for four years. The council reported that during the period between July 2016 and February 2017, when no fine was imposed, 67,945 overdue library items were returned. This was more than triple the number of overdue items returned in the previous 12 months. This showed that without the threat of a financial penalty for overdue books, three times as many (almost 70,000) were returned to their libraries.

In 2017, the City of Sydney Council undertook a trial which led to a moratorium on library fines for four years. The council reported that during the period between July 2016 and February 2017, when no fine was imposed, 67,945 overdue library items were returned. This was more than triple the number of overdue items returned in the previous 12 months. This showed that without the threat of a financial penalty for overdue books, three times as many (almost 70,000) were returned to their libraries.

Clover Moore, Lord Mayor for the city at the time, referred to fines as,

“an additional cost to the community”, “acting as a disincentive for borrowers”. "[We've] found that, in most cases, [fines] had the opposite effect, frightening members into never returning their overdue items."

Driving Offenses

To evaluate the deterrent efficacy of fines, the most common penalty imposed in New South Wales (NSW) for criminal convictions, the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research examined the history and subsequent reoffending of 70,000 persons who received a court imposed fine for a driving offence between 1998 and 2000.

The analysis failed to find any evidence for a significant relationship between the fine amount and the likelihood that an offender will return to court for a new driving offence. Nor was there any evidence to suggest that longer licence disqualification periods reduced the likelihood of an offender reappearing before the courts.

The study identified that there were three main reasons as to why variations in fine amounts might have limited efficacy in deterring offenders:

- The vast majority of potential offenders may be deterred by the anticipated informal social sanctions associated with public exposure of the offence rather than the formal punishment prescribed by legislatures.

- There may be no marginal deterrent effect of higher fines at existing fine levels.

- Many offenders may discount the penalty because they believe the risk of detection and apprehension by police to be very low.

Moral behaviour and materiality

Samuel Bowles, Director of the Behavioural Sciences Program at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, believes that,

"certain cues can switch moral behaviour on or off".

In a recent study, Bowles concluded that fines can undermine an individuals sense of ethical obligation with these traits becoming "just another commodity" to purchase.

Classical deterrence theory goes some way to support this by proposing that an offender will engage in criminal behaviour if they believe that the benefits they will derive from the crime outweigh the costs associated with being caught. The effectiveness of fines in achieving a deterrent effect is thought to depend upon the certainty, severity and speed of punishment. If people perceive it likely that they will be caught for an offence and receive harsh and swiftly delivered punishment, then they will be less likely to offend (Becker 1968; Gibbs 1975; Zimring & Hawkins 1973).

Therefore the question arises as to whether the financial penalties, which have and are expected to be imposed on those considered to be the most significant offenders from the BRC, could ever be sufficient enough to alter the moral behaviour of those who designed, approved and implemented the practises in question and, in some instances, intentionally misled customers and the regulators in order to continue with them.

From the behavioural economic studies above, there is also the potential that organisations, such as the big four banks can now put a 'price' on not collecting your child on time, not returning a book, or not driving within the speed limit. In doing so, they could begin to rationalise behaviour and cultures which disadvantage customers through cost/benefit analysis’, and the potential that, should the commission not be extended, the likes of ASIC and the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) could focus on damage limitation and self-preservation as opposed to investigations into otherwise unreviewed areas of their business.

From the behavioural economic studies above, there is also the potential that organisations, such as the big four banks can now put a 'price' on not collecting your child on time, not returning a book, or not driving within the speed limit. In doing so, they could begin to rationalise behaviour and cultures which disadvantage customers through cost/benefit analysis’, and the potential that, should the commission not be extended, the likes of ASIC and the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) could focus on damage limitation and self-preservation as opposed to investigations into otherwise unreviewed areas of their business.

The interim report found that infringement notices imposed penalties that were immaterial for the large banks. Enforceable undertakings might require a 'community benefit payment', but the amount was far less than the penalty that ASIC could properly have asked a court to impose.

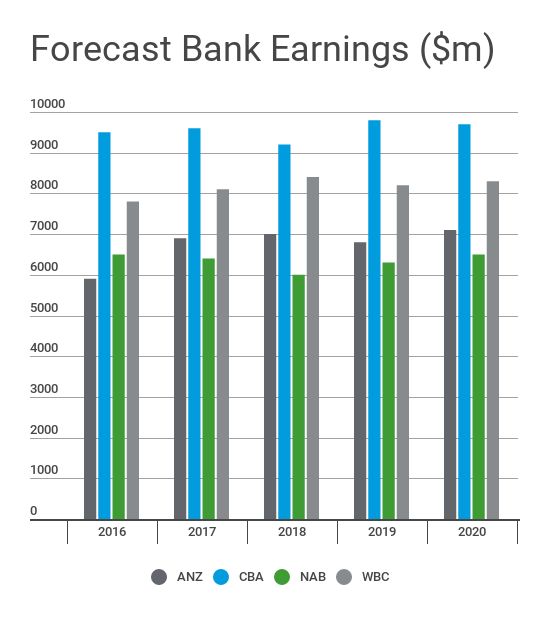

In addition to the $1.3 billion estimated by Morgan Stanley for fines and customer remediation programs, an additional $1.1 billion is expected in compliance costs bringing the total financial implication of the BRC to $2.4 billion.

The same Morgan Stanley research suggests that this represents only about 2.5 percent of the expected $90 billion in cash profits the banks are expected to earn in the next three years. Whether this is a sufficient deterrent to be a catalyst for change, or a means to justify the pursuit of short-term profit at the expense of basic standards of honesty, only time will tell.

Source: Morgan Stanley Research

For more information about the Banking Royal Commission, please get in touch with your local RSM adviser.

Find your local RSM Adviser >>

References

Gneezy, U & List, J . (2012). The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and the Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life, Hachette Australia

Shefrin, H. (2002). Beyond greed and fear: Understanding behavioral finance and the psychology of investing . Retrieved at: (https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hX18tBx3VPsC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Shefrin+(2002)+three+prevalent+themes+in+behavioural+economics&ots=0vs7ewyt-z&sig=Iinru4h2cG8V_RAF_pXwO7KUL0E)

Bowles, S. (2008). Daycare late fees no deterrent, study finds. Retrieved at: https://www.thestar.com/life/health_wellness/2008/07/04/

daycare_late_fees_no_deterrent_study_finds.html

Letts, S. (2018). Banking royal commission: How much will their misbehaviour cost the banks? Retrieved at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-09-14/bank-royal-commission-how-much-will-misbehaviour-cost-the-banks/10246846

Becker, G. (1968). Crime and Punishment: An Economic Apporach. Retrieved from: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c3625.pdf

Gibbs, J (1975). Crime, Punishment and Deterrence. Retrieved from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002242787601300209?journalCode=jrca

Zimring, F & Hawkins, G. (1973). Deterrence – The Legal Threat in Crime Control. Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=10857

Visentin, L (2017). City of Sydney shelves library fines for four years after 70,000 overdue items returned. Retrieved from: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/city-of-sydney-shelves-library-fines-for-four-years-after-70000-overdue-items-returned-20170707-gx6lcl.html