You call that a diverted profits tax? This is a diverted profits tax…

Australia’s Federal Treasurer Joe (‘Crocodile Dundee’) Hockey announced on Monday 11 May 2015 that the Federal Budget will contain two new major integrity measures.

The first measure aims to restore Australian taxing rights over 'stateless' income which originates in Australia by ‘deeming’ a taxable presence. The second will apply GST to digital material downloaded from ex-Australian suppliers and currently escaping Australian GST (colloquially dubbed the ‘Netflix Tax’). No mention was made of the ATO’s ‘formula’ for calculating effective tax rates (‘ETRs’), as discussed in a recent Tax Alert.

1. Restoring Australian ‘taxing’ rights on ‘stateless income’

The Treasurer’s release confirms Australia will not follow the UK in imposing a ‘diverted profits tax’ (DPT); apparently, the UK and Australian tax systems are too different. Instead, Australia will strengthen its anti-avoidance laws (by which we understand the Treasurer to be referring to Part IVA, the general anti-avoidance rule) with a particular focus on arrangements which attempt to re-source income away from Australia, and deny Australian taxing rights.

The initiative will re-establish, or deem, an Australian taxable presence to which the Australian originated sales revenue will be attributed, and then subject to Australian tax.

This measure targets the same practices as the UK’s DPT, but does so in a much more ‘robust’ manner. Australia will legislate this as ‘tax avoidance’ of the first order, despite the fact that the countries participating in the BEPS process have all agreed this is a grey area, and in many cases will actually comply with exiting international tax norms.

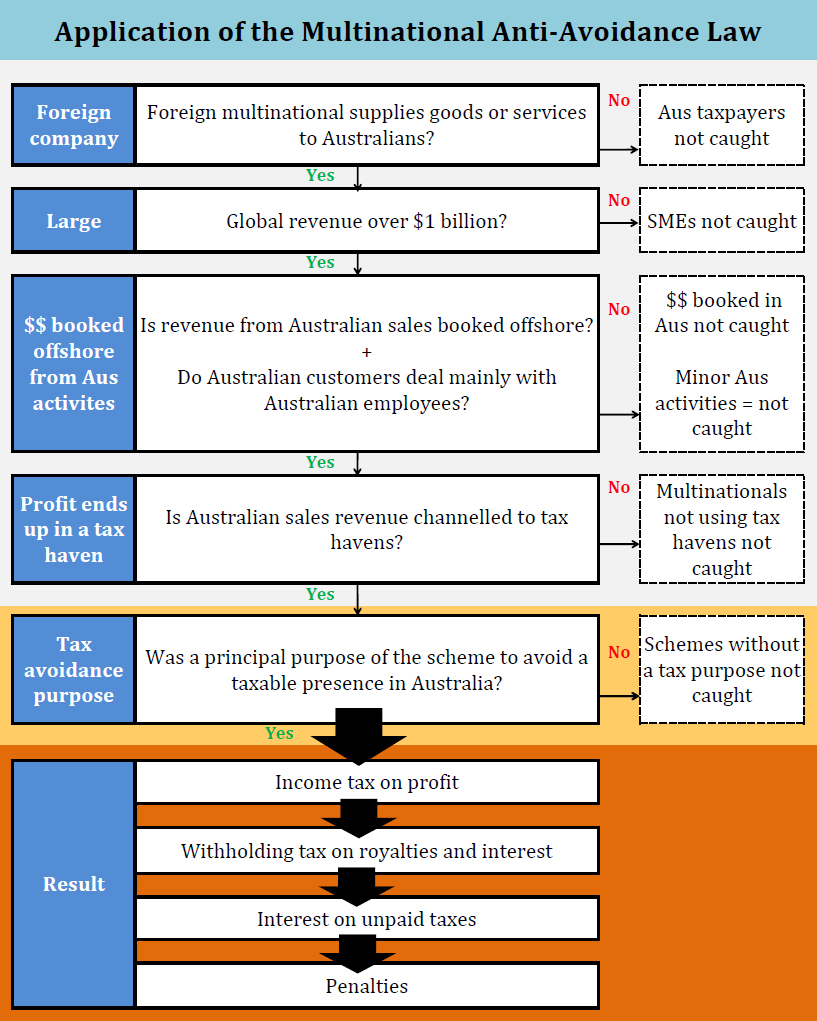

This new measure is aimed at the activities of “30 identified multinational companies”, all of whom are non-Australian. The key elements of the proposed measure are:

- targets: aimed at foreign multinationals, not Australian groups

- de minimis threshold: multinational group global revenue must exceed A$1bn

- nexus: do Australian customers deal mainly with Australian employees of the multinational group, AND are the Australian sales revenues effectively booked by group companies outside Australia?

- tax burden: does the Australian sales revenue end up in a tax haven, having borne little or no global tax

- purpose test: was the principal purpose of the arrangement to avoid a taxable presence in Australia?

If yes to all of the above, penalties equal to 100% of the avoided tax can be levied, as well as collecting the unpaid tax, and charging interest. The temperature is about to go up in the kitchen!

This Australian ‘initiative’ should not be subject to one of the major criticisms levelled at the UK DPT: the legitimacy of the DPT.

The UK DPT has all the characteristics of a new tax, which the UK is precluded from introducing because of its existing treaty commitments. (The UK, of course, disputes this.)

But Australia is on firmer ground. If as expected, this integrity measure is enacted through Part IVA, then Australia is not in contravention of its treaty obligations: Australia’s treaty commitments are subject to Part IVA, in other words, Part IVA takes priority over the terms of double tax agreements.

But whilst on firm legislative ground, Australia becomes the second member of a select group of sovereign nations which have thumbed their noses at the concept of global consensus action on BEPS. This is all the more remarkable when one considers that the very issue of ‘taxable presence’ is at the heart of the BEPS Action 7 recommendations – but Australia has pre-empted that global response.

And it is this unilateral move which is likely to put Australia in direct conflict with the US. At the heart of the technical issue is this – whose tax is actually be avoided by these international structures? Australian tax or US tax?

Mr Hockey is saying it is Australian tax which is being avoided, but is that the case? The US has a very good case for arguing its own tax is that which is avoided.

Consider if Microsoft delivered its software to Australian customers by download from the US, and accounted for the Australian sales revenues in the US books (and paid tax on those sales in the US). Would Australia be as robust in claiming taxing rights over that income? Almost certainly not, but the result seems to be different where the sales revenues are booked in Singapore.

One begins to get the sense of an opportunistic tax grab by Australia, which could be anticipated to be vigorously resisted by the US. It is precisely this type of ‘tax war’ which the OECD’s global consensus approach aims to avoid.

The following table accompanies the Treasurer’s press release.

Source: Strengthening our taxation system, Media Release, 11 May 2015

2. ‘Netflix’ tax

It is surprising this development is ‘dressed up’ as an integrity measure aimed at multinational tax avoidance; it is not, but perhaps given the Senate’s disposition to reject any and everything, the political ‘optics’ require it to be clothed as an anti-avoidance measure.

The truth is far more prosaic.

We all know the expansion of the digital economy has facilitated the remote delivery of ‘digital material’, without the need for a foreign supplier to have any meaningful presence in Australia. This advantages non-resident suppliers, over resident registered suppliers, particularly in the area of indirect taxation. How can Australia apply GST to an Australian individual’s digital download of an e-book, an e-game or e-music where the supplier is outside Australia?

Taxing the individual consumer is within the sovereignty of the Australian Government, but is that practical or realistic?

The OECD has been working on this matter for many years, and has issued its ‘International VAT/GST Guidelines’, which lay down the ‘destination principle’ as the appropriate basis for levying indirect taxes. That is to say, tax should be paid in the country where the consumer is resident (in our case, Australia) and where the consumption is enjoyed, but the tax should be paid by the non-Australian supplier.

These guidelines are not new – but how can Australia effectively make non-Australian suppliers register and act as collectors of Australian GST?

The European Union has been doing it for some years, and the evidence from the EU is that it has taken some time to catch on, but non-EU suppliers are now working to become compliant.

The same will (eventually) occur in Australia, and we should recognise Australia is a single country which will make the implementation much easier than in Europe – where so many different sovereign taxing jurisdictions exist cheek by jowl, with all the inherent compliance complexities that entails.

If Australia follows the OECD VAT/GST Guidelines, then:

- foreign suppliers should be able to register through a ‘simplified’ registration regime

- foreign suppliers will only need to account for GST (and therefore include it in the price) where the supply is made to an unregistered Australian person (i.e. an end-consumer)

- where downloaded supplies are made to Australian GST registered businesses, no GST will be charged by the foreign ‘supplier’ – the Australian recipient will continue to self-assess a reverse change

Whether this is a ‘change’ to the GST rules which requires support from all Australian Governments, or whether it is a technical fix, seems a moot point, as we understand all Governments have indicated support for the change.

(But no word on any reduction in the low value GST threshold on physical imports.)

With the recent tax-related announcements, one can wonder what, on the tax agenda, can be left for discussion in the Budget paper to be released on Tuesday, 12 May 2015.