The reliability of a valuation conclusion heavily hinges upon the assumptions and inputs used in the exercise. Often, failure to consider critical factors such as the lack of understanding of valuation theory, mechanical application of valuation theory or over simplification of assumptions result in material misstatements in value. This article highlights some of the common pitfalls when reviewing valuations.

1. Insufficient consideration of impacts from COVID-19 and seasonality

The COVID-19 outbreak has brought about many uncertainties, increasing the complexity of projecting future cash flows. Using historical results is a common starting reference in the projection of future financials. Nonetheless, the pandemic has caused major disruptions to many industries, bucking any trajectory a business may originally had been on if not for such extraordinary times. This inevitably results in distortions in financial performance, be it in revenue growth or profitability margins, necessitating careful consideration of the impact of COVID-19, both historically in 2020 and 2021 and going forward from hereon.

Issues that typically arise include:

Using 2020 or 2021 as a base to forecast future revenues

It is common for businesses that are relatively stable to apply a sustainable growth rate, such as the expected inflation rate or GDP growth rate, to revenues from the latest financial year. However, given that 2020 and 2021 are anomalous years, doing so without careful scrutiny of revenue drivers going forward may yield results that end up being highly inaccurate.

This is especially so for businesses that have benefited from the effects of COVID-19, for instance e-commerce businesses and food processing businesses. Careless application of a sustainable growth rate to possibly unsustainable 2020 or 2021 revenues can cause material overvaluation of the business due to a very likely possibility that revenues may actually fall in the short term as business returns to normal and positive effects from COVID-19 wear off.

Using 2019 as a base for business as usual

Very often, when thinking about post-COVID-19 normalisation, it is common for companies to project that businesses will return to 2019 levels in the short term, the rationale being 2019 is a year that precedes the onset of COVID-19.

Much less considered is the question: Will that be the case?

For instance, are the revenue drivers resulting from COVID-19 going to be a new normal or are they merely temporary or perhaps a combination of both? Critically, will the dynamics of the business environment be different?

With work-from-home arrangements being a new normal during this COVID-19 period, some employers have looked to having hybrid work arrangements in the future where employees will work from office for only part of the week. F&B businesses in the Central Business District may therefore expect lower business volumes going forward compared to 2019, even after the lifting of COVID-19 working and dining restrictions.

As such, due consideration is needed when projecting whether revenue and profitability will return to a level similar to pre-COVID-19 period.

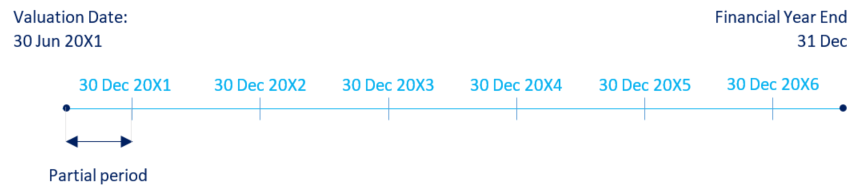

Another issue that is commonly missed is seasonality in a business. The commencement of cash flow projections is based on the valuation date of the exercise. As such, situations may arise where the valuation date is different from the financial year end of the business, resulting in the need to project cash flows for a partial period (see illustration below).

For seasonal businesses which experience a spike in activities during certain months of the year, mechanical extrapolation of the partial period prior to the valuation date will result in a skewed projection. For instance, a retail business may expect high business volume in June and December due to mid-year and year-end sales. Assuming a valuation date of 31 May 20XY and a financial year end of 31 December 20XY, simply extrapolating the first five months of revenues to seven months for June to December will materially understate the revenues projected for the period.

While it is often the case that historical financials are analysed on an annual basis—in cases where seasonal businesses and partial periods are involved—it is important to analyse quarterly or even monthly financials in order to take into account fluctuations in business activities.

2. Using net income as a proxy for free cash flows in a discounted cash flow model

In general, the value of a business equals to the present value of all future cash flows expected to be generated by a company. In our review of discounted cash flow models, it is common for companies to use other metrics in place of cash flows to the firm. For instance, a common proxy used is the net income. However, this can be quite different from free cash flows to the firm and erroneous when valuing the company.

Net income on a company’s income statement is generally prepared in accordance with IFRS/GAAP which is based on accrual accounting. This aims to match revenues to expenses in the period where they are earned or incurred, as opposed to when cash flows are received or paid. As such, net income has to be adjusted in order to be converted to cash flows, which includes:

- adding non-cash items, such as depreciation and amortisation expenses;

- adding finance expenses;

- subtracting required capital expenditure for the maintenance of existing property, plant and equipment (“PP&E”) or to purchase the new PP&E to expand the business; and

- subtracting the required investment in working capital (i.e. trade receivables, inventory, trade payables, etc.).

3. Double-counting of risk in cash flow and discount rate

A valuation exercise, regardless of approach, is based on the combination of inputs and assumptions. However, many a time, inputs and assumptions (inconsistent with each other) are applied to a valuation. Care should be taken to avoid any double counting of risks, for example additional risk premiums are not required for factors that have already been addressed in cash flows.

For instance, where expected cash flows in the short term have been reduced to account for uncertainty due to COVID-19 measures, an additional risk-premium for uncertainty arising from COVID-19 should not be included in the discount rate.

Likewise, when it comes to valuing emerging market companies, care should be taken not to over-count country risk. For instance, if one was to use a higher discount rate to reflect country risk and at the same time haircut expected cash flows to reflect the same country risk, one would be double counting the risk of operating in an emerging market.

4. Omission of non-operating assets when estimating equity value

Under FRS 36, a cash-generating unit (e.g. a product line or a subsidiary) is impaired if its carrying amount exceeds its recoverable amount, the latter being the greater of its fair value less disposal costs or its value in use. In assessing the recoverable amount, one looks at the present value of future cash flows expected to be derived.

When making a comparison between the carrying amount and recoverable amount, one has to ensure the comparison is on a like-for-like basis. In assessing the recoverable amount, free cash flows to the firm only captures the value of core operations of a company i.e. the enterprise value. To get to the equity value of a company, non-equity claims on the firm have to be subtracted. These claims include interest bearing liabilities, shareholder loans or hire purchase. Cash and other non-operating assets on the other hand will be added to the value. This should be compared with the carrying amount captured under the balance sheet under investment in subsidiary. It would have been erroneous to compare the enterprise value with the carrying amount as it would not be a like-for-like comparison.

Keeping an eye out for pitfalls

The process for valuing a company is often riddled by complexities, and requires robust consideration of granular factors in order to achieve a sensible and supportable conclusion. Given that a valuation hangs upon the selection of inputs and assumptions, one can easily risk arriving at a garbage-in-garbage-out value where pitfalls fail to be recognised by the valuer. As the proverbial saying goes, the devil is in the details. With valuations having high stakes in play, it is all the more important to accord commensurate attention to them or to engage an experienced valuer who can help with your valuation.